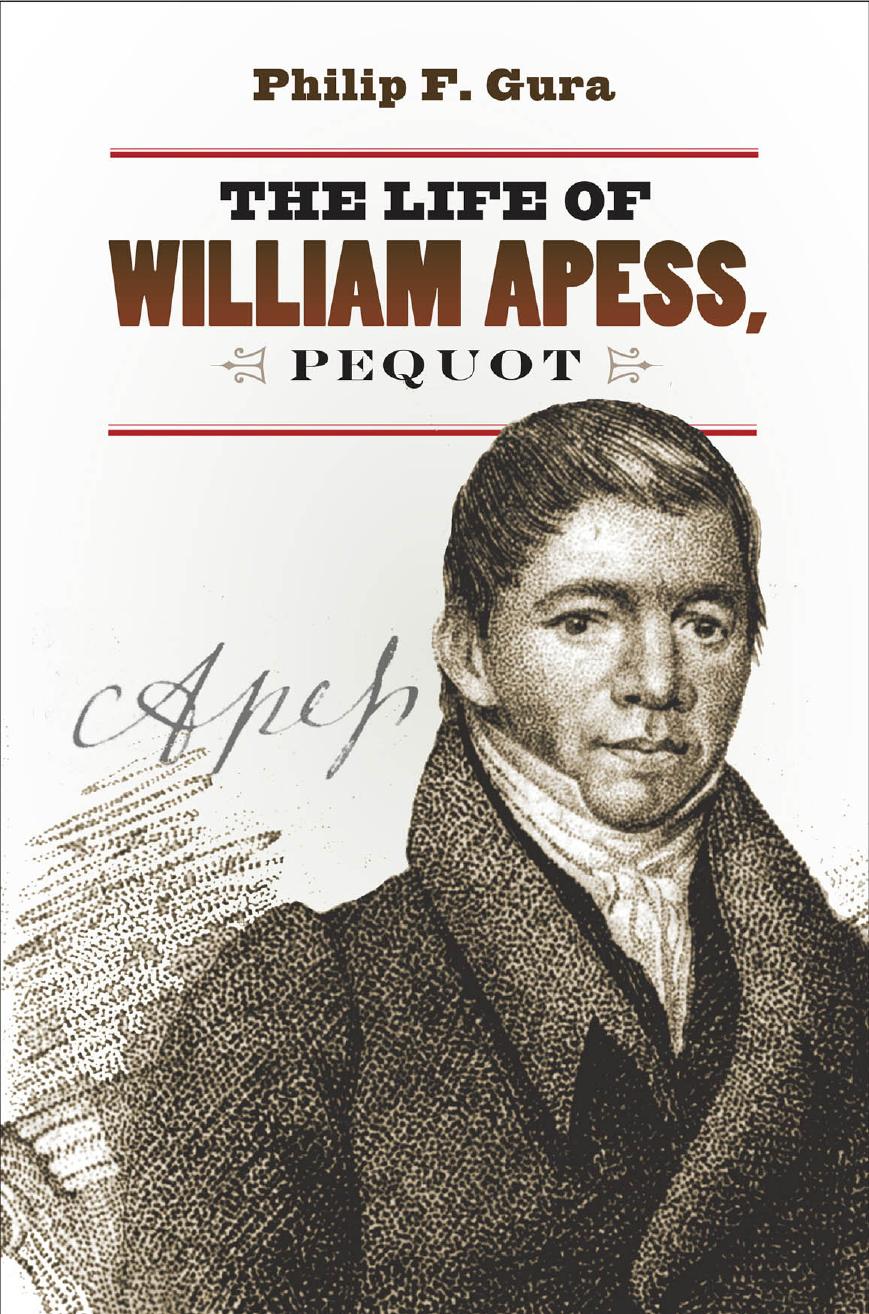

The Life of William Apess, Pequot by Philip F. Gura

Author:Philip F. Gura

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Published: 2018-06-20T00:00:00+00:00

MASHPEE TRIUMPH

That spring, the General Court finally debated the Mashpee petition, even as histrionics against them continued in the newspapers. The legislators’ investigative committee consisted of “Messrs. Barton and Strong” of the Senate and Dwight of Stockbridge, Fuller of Springfield, and Lewis of Pepperell from the House. Hallett represented the Indians, whose list of witnesses included Deacon Isaac Coombs, Daniel Amos, Ebenezer Attaquin, Joseph B. (Blind Joe) Amos, and Apess himself from the tribe; and only one white man, Lemuel Ewer of Sandwich. On the other side, Kilburn Whitman of Pembroke served as counsel for the overseers; and J. J. Fiske of Wrentham and Elijah Swift of Falmouth, both on the Governor’s Council; the Reverend Fish himself; Judge Marston Nathaniel Hinckley and Charles Marston of Barnstable; Gideon Hawley of Sandwich; Judge Whitman of Boston; and two Mashpees, Nathan Pocknet and William Amos, appeared as the overseers’ witnesses. These last two, Apess claimed, were those with whom the overseers had made friends “in order to use them for their own purposes” (228–29).

In subsequently describing Fish’s testimony, Apess disputed the clergyman’s supposed commitment to his mission. He also ventured onto hitherto unexplored ground, commenting on sexual relations between members of different races because the topic “had been rung in [his] ears by almost every white lecturer [he] ever had the misfortune to meet.” Apess doubted that any missionary ever really sought to make “the Indian or African” his equal for precisely that reason: as soon as the issue of equal rights arose, “the cry of amalgamation is set up, as if men of color could not enjoy their natural rights without any necessity for intermarriage between the sons and daughters of the two races.” He assured readers that Mashpee men had less inclination to seek the white men’s daughters than they did the Indians’ own. Returning to rhetoric he had voiced in his “Looking-Glass,” Apess asked, “Does the proud white think that a dark skin is less honorable in the sight of God than his own beautiful hide?” It seemed to him, he continued, “that it is more honorable in the two races to intermarry than to act as too many of them do,” that is, to consort together outside of marriage. His advice to whites was, “Leave the colored race alone” unless they really did wish to “ marry our daughters, and [then have] no more ado about amalgamation” (230–31).

Hallett’s presentation, befitting an attorney, was thorough, reasoned, and fact filled. After describing the Reverend Fish’s dereliction, he praised the recent activities of the Baptist minister, Blind Joe Amos, whose ordination the overseers had not even allowed in the Mashpee meetinghouse; the ceremony had taken place in a private home. Hallett also mentioned the Mashpees’ sincere interest in religion, for, in addition to having the benefit of Amos’s tutelage, they now also could attend the services of the “Free and United Church” that Apess had started. In fact, he reminded the legislature, in two years Apess and Amos had brought in more church members than Fish had netted in two decades.

Download

The Life of William Apess, Pequot by Philip F. Gura.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Becoming by Michelle Obama(10032)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5768)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5643)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4612)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3996)

The Five People You Meet in Heaven by Mitch Albom(3575)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3548)

The Choice by Edith Eva Eger(3473)

Full Circle by Michael Palin(3455)

The Mamba Mentality by Kobe Bryant(3289)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3039)

Imagine Me by Tahereh Mafi(2972)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2943)

The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande(2863)

Less by Andrew Sean Greer(2701)

A Burst of Light by Audre Lorde(2614)

The Big Twitch by Sean Dooley(2440)

No Room for Small Dreams by Shimon Peres(2375)

Everest the Cruel Way by Joe Tasker(2347)